Soundtrack for an Unbuilt City

Sonic Imaginaries of New Babylon!

New Babylon is possibly the most significant unbuilt city of the twentieth century. Its creator, the Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys, insisted for most of the two decades he spent speculatively making hundreds of models, photographs, drawings, films and other artworks depicting elements of it, that New Babylon was not a utopia but a realisable plan for an actual urban form. He only relenting late in the project, when he felt that the developing social, political and economic conditions made its manifestation impossible.

So much has been written about the project since the artist called a halt to its production in 1974 that it would be redundant to re-describe it here, apart from briefly ...

In architectural terms New Babylon consisted, in the words of David Pender, one of its most insightful and thorough historians, of

“a giant space-frame, raised up from the ground by means of pilotis or as a suspended or self-bearing structure”.

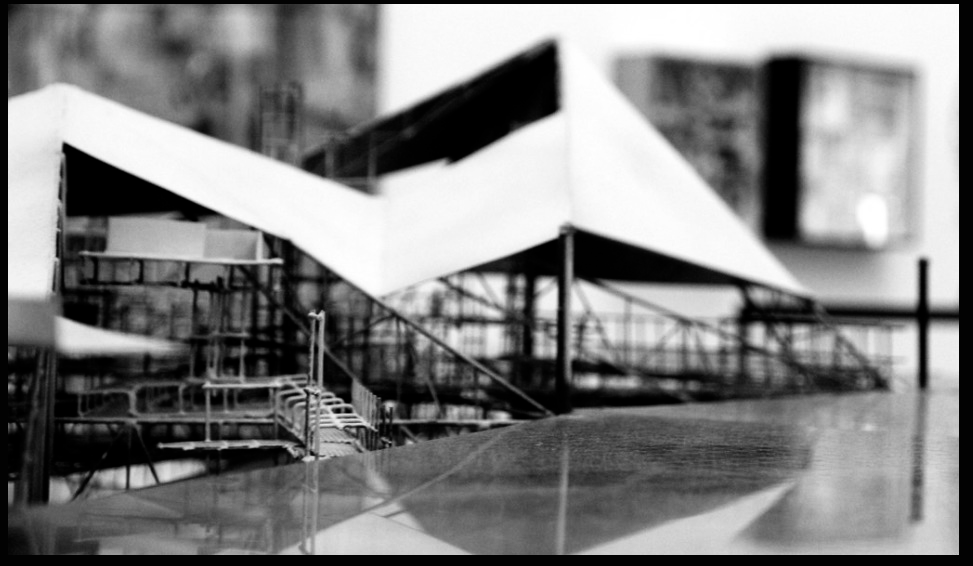

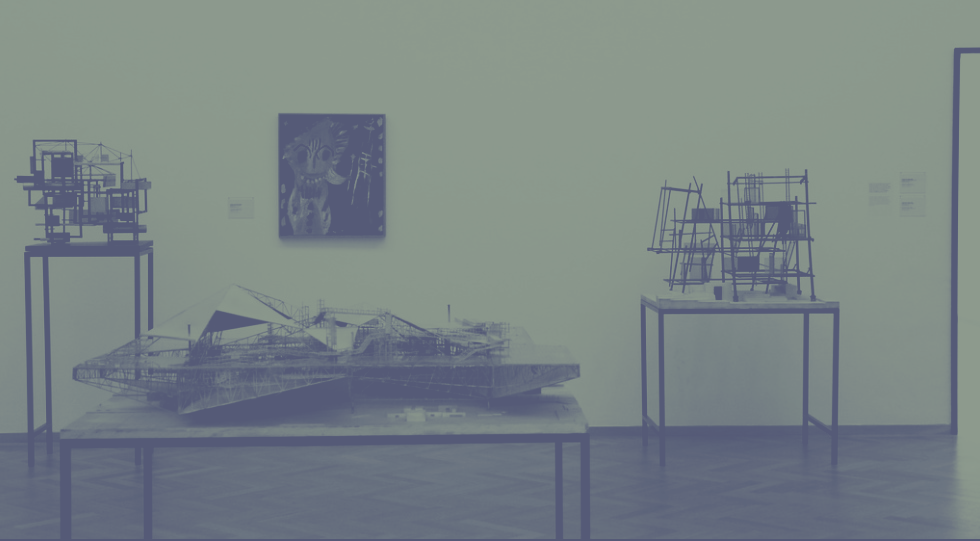

The space-frame supported the city’s main units “covered and horizontal units known as sectors”, each of which “might be around ten to thirty hectares in area, several stories high and raised about fifteen or twenty metres above the ground … interconnected internally by stairs and lifts.” Constant’s models, fabricated from metal, wire, plexiglass, oil paint and ink, represented various sectors and have been described as “extremely sophisticated architectural statements” and have exerted a well-documented influence - along with that of the entire visionary project - on subsequent experimental and radical architectures. It has even been implied that an interview with Constant influenced Rem Koolhaas’s decision to take up the profession.

The city’s spatial separation from the ground below mirrored the elevated consciousness of New Babylon’s inhabitants, citizens of a post-capitalist society in which work had been abolished thanks to ever-accelerating automation [a strand of Marxist theorising known as ‘accelerationism’, which has had a recent, if controversial revival]. Emancipated to release their inherent creativity, New Babylonians - willing serial migrants - would wander the city permanently. Within the larger framework which potentially proliferated to span the globe, micro-structures could be reconfigured, moved and customised with sound, lighting and networked communications technology in response to the temporary dweller’s creative impulses. The result would be a poetic urbanism as Constant envisaged: “One crosses cool and dark spaces, hot, noisy, chequered, wet, windy spaces under a bare sky, obscure corridors and alleyways, perhaps a glass grotto, a labyrinth, a pond, a wind tunnel, but also rooms of cinematographic games, erotic games and rooms for isolation and rest.” As his widow Trudy van der Horst recalls “He was interested in the culture people would make when they are liberated.”

Constant, as he preferred to be known, was a restlessly experimental innovator. A founder, member, or close associate of a succession of radical artistic, urbanistic, aesthetic, technocratic and even political groupings, he nevertheless retained a strong streak of individualism throughout the development of both his artistic practice and personal convictions. He had, in the words of van der Horst a “dialectical personality.” The meeting of an early grouping, the Dutch Experimental Group, foregrounded a perennial feature of the artist’s life: the role of music. Constant had been an excellent musician and singer from an early age and at the Group’s gatherings, where “they often dress up and play gramophone records or live music”, he showed himself to be “a talented guitarist with an extensive repertoire, including Spanish improvisations.” There are later photographs of him playing violin and, notably, the cymbalom, a large dulcimer-like instrument associated with gypsy music which he learned in middle age. When he died in 2005 he owned a total of 36 musical instruments; equally eclectically, his record collection ranged across Varèse, Cage, Charlie Parker, Hungarian and Romanian gypsy songs, flamenco, English lute music, Bartók, electronic music, Schubert, Bach and the classical canon.

Which brings us to a glaring, yet apparently unexplored, paradox in relation to New Babylon; why did this profoundly, perennially musical man have so little to say about the sonic aspects of his elaborately envisaged future city?

The senses as a whole played a major role in New Babylon and in the broader theory of a revolutionary urbanism that lay behind it.

In November 1952 Constant made a working visit to London, with a side trip to the artists’ outpost of St. Ives in Cornwall. He met Henry Moore, Alan Davie, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Victor Pasmore and Roger Hilton and other artists. In vivid contrast to the highly receptive art climate in London, he was shocked by the widespread damage, which directed his thinking towards the role of art in postwar reconstruction, and, perhaps more crucially, brought home to him the profound effect on the senses that the urban environment imparts, especially in extreme circumstances. As a result, Constant reoriented his artistic practice towards architecture, connecting with movements like the Congrès Internationaux d’architecture Moderne and the Liga Nieuw Beelden [League for New Representation] and collaborating with architects such as his friend and colleague Aldo van Eyck. These various associations shared a rejection of Corbusier’s rational modernism, the aesthetic of the block and the grid that characterised much postwar reconstruction:

“I realised that … all around us entire neighbourhoods had been built that were part of that ‘abstraction froide’: straight lines, steel frames, huge concrete surfaces. I wanted to explore that terrain for myself, in an aesthetic sense. That eventually brought me to New Babylon.”

Before that stepping-off point, Constant’s urban focus had already started to manifest itself in quasi-architectural experiments and innovations. Van Eyck involved him in an exhibition, 'Mens en huis' [Man and House] at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. In 1954 Constant designed a “model interior” with the architect Gerrit Rietveld for the De Bijenkorf store’s furniture department, and later that year, along with British artist Steven Gilbert and French/Hungarian sculptor Nicolas Schöffer, he formed the short-lived néovision, producing collaborative three-dimensional sculptures – including the sixteen-metre tall Monument for Reconstruction for the E55 energy exhibition in Rotterdam.

Not only does the néovision manifesto propose a synthesis between art and architecture, it incorporates elements of innovative technology, prefiguring the foundational, though mostly implicit, role of new communications technologies in New Babylon.

Constant’s best-known group association – and the one that would have the most profound influence on his developing sense of an alternative urbanism – was yet to come.

In 1956, he travelled to Alba in the Italian Piedmont, to attend a conference on ‘Industry and Fine Arts’ as an architectural specialist, to deliver a lecture he titled Demain la poésie logera la vie [‘Tomorrow, life will reside in poetry’]. There he met writer, filmmaker and activist Guy Debord, founder of the Paris-based Lettrist International movement, and they decided to launch the yet more radical group which became the Situationist International [SI]: a vehicle for their shared belief in a new ‘unitary’ practice of urban planning that integrated art and technology while rejecting consumerist consumption, work and modernist rationalism.

Along with Debord, Constant was captivated by the notion of homo ludens, ‘Man the player’, the title of a 1938 book by the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, and subtitled 'A Study of the Play-Element in Culture'. The Situationists turned Huizinga’s ethnographic analysis into a mission; the creation of a society of creative play.

But how was that to be realised? A key tool was a practice which the Lettrists called ‘psychogeography’, a technique of urban exploration and a way of understanding how the planning and design of the city determined the psychological states of its inhabitants.

Postwar, behavioural scientists developed the concept of the learning labyrinth, a space which induced ‘unlearning’ or ‘deconditioning’ in its visitors. Constant and his colleagues were keen to build one, designed to make “orientation truly impossible” by using false perspectives, phony maps, wonky lighting, fake windows, literally misleading signage and a team of pretend visitors offering disorienting messages and encounters. A version of the concept was realised in 1965 by the Experimental Studio Rotterdam [ESR], an architectural think-tank set up by Constant in the port city using funding from a state-supported construction industry body, the Liga Nieuw Beelden [League for New Building]. A photograph of the installation, showing young people playing and striking poses on the structure, appeared as a centrefold image in issue #4 of Provo, the magazine of an anarchist group of the same name that, like the ESR, emerged in Amsterdam in 1965. Sharing a critique of capitalist urbanism and a desire to replace work with play brought Constant close to the Provos, resulting in an invitation to edit Provo #4. The predominantly youthful group adopted him as a sort of guru.

The ESR labyrinth installation foregrounded a prominent characteristic of the various cohorts of artists with whom Constant had associated; a rejection of any hierarchy of media or technique.

They repudiated the primacy of painting in the Western artistic tradition – despite many members being painters – leaning instead towards a media-agnostic vision of artistic creativity, a strong current in Constant’s own practice that showed clearly in the ESR labyrinth and in his ‘Schema of Ambient Construction’ that informed it. It was immersive and “multisensorial": along with a work space and various physical elements, it included both a ‘odoratorium’ and a ‘sonorium’, presumably spaces where participants were subject to psychologically transformative inputs of smell and sound.

Through these smaller built environments and in the totality of New Babylon, Constant made the behaviourist leap from an analytical understanding of the urban environment’s effects on human senses and psychology to the deliberate manipulation of them,

a mission entirely in keeping with the intertwined radical cultural and political movements in 1960s Amsterdam. The city’s experimental music scene, for instance, often rejected any sense of responsibility for listeners’ enjoyment, or even comprehension. When the composer William Breuker staged a series of lunchtime concerts for three barrel organs in Amsterdam’s central Dam square in the summer of 1967, he “made no concessions to the general audience who happened upon the performance.” Press reports recorded “the perplexity and anger of many passers-by.”

Similarly, in the lectures that Constant was invited to give as the speculative vision of New Babylon began to gain traction in artistic and architectural circles, he actioned his belief that “art should awaken”, doing so not just visually but more abrasively with sound.

The lectures were frequently complemented by a slide show or film and a recording, or ‘sound-tape’, of what are usually described as ‘sound effects’, adding up to an “intense visual and audio experience”. For Constant, this was a way for the audience to visit “a new and unknown city and to undergo its specific atmosphere.” As one account has it:

“The lights go out, the room is filled with unintelligible ambient music as slides of densely layered architectural plans of impossible scale are projected upon the wall.”

At another event in February 1968, The Birmingham Post reported that the sides were “accompanied by a soundtrack of music, car and aeroplane engines and an assorted cacophony of other noises so painful that one could only hope that this was a row we should be escaping from and not going to."

This description matches very closely the soundtrack that introduces a 1962 film/interview with Constant featuring poet and television presenter Simon Vinkenoog, suggesting, along with the presence of improvised guitar, that the artist himself could have been involved in their production.

Opening with footage of a passenger plane coming in to land, the sound-bed segues from a dense cacophony of overlaid radio transmissions that escalate to a state of almost-white noise into randomly plucked guitar strings over background chatter, bumps and outbursts of singing that evoke a rowdy drinks party.

The guitar turns atonal and hammers out a flat, mechanistic rhythm, before giving way to a melange of abstract machine noise, a clattering train and a mangled brass band, prefiguring the sonic mash-ups and productive dissonances that would become standard features of both popular and experimental music in the second half of the twentieth century and are implicit in the film’s soundtrack, which resembles, if anything, crude raw material gathered for Holger Czukay’s pioneering classic of analogue cut-up recording, 'Cool in the Pool'.

Here, though, clues as to the sonics of New Babylon diverge sharply, not least in the musical personality of Constant himself. Despite declaring that “Industrial and machinic culture is an indisputable fact and artisanal techniques … are finished”, he nevertheless played guitar, violin and cimbalom, adoring improvised gypsy music which was performed at his wedding to Trudy. In his personal life, music was a craft that encouraged social and creative community, an essentially human practice. However, given his inherent musicality, the experimental multi-media practice of many of his collaborators over the years [one Cobra artist, Karl Appel, recorded an album of full-on musique concrete at Amsterdam’s Instituut voor Sonologie in 1963], along with his immersion in the radical culture of Sixties Amsterdam and his championing of technology, it seems positively perverse to think that Constant didn’t embrace the emerging electronic music of his time in some way. Given his archive is still being carefully compiled by his widow Trudy and her daughter Kim, this may not be the last word on the subject; a device recently unearthed in the basement of Constant’s house might be a homemade sound mixer and the reels of tape that are yet to be digitised could provide evidence for the production of further soundtracks.

Constant’s son Victor, who made fly-through films of New Babylon for which he also created bricolage-style soundtracks, may have also been the producer of the taped ‘sound effects’ that disoriented those attending the artist’s lectures. In 2005, the year of Constant’s death, Victor and his filmmaking partner Maartje Seyferth made a short film designed to give “an impression of the experience of the New Babylonians”. Victor is credited with the unsettling ‘soundmix’, which blends electronic atmospherics with abstract noises and voices, distorted brass band music [again], gypsy voice and violin, acoustic guitar, sitar, musique concrete, what is most likely a fragment from a live recording of AC/DC’s Whole Lotta Rosie and a snatch of ‘African drumming’ from the library music album Sounds of Horror, Sci-Fi, the Weird. Another filmmaker, the American Hyman [‘Hy’] Hirsh whose work combined abstract visuals with contemporary music, created the 1958 experimental film Gyromorphosis by animating and layering stills of Constant’s models, adding ‘colour lights’ and setting the result to a track by the Modern Jazz Quartet. Music was central to Hirsh’s aesthetic – more accurately described as synaesthetic, given the goal of establishing ‘the visual equivalent of music’, a current in twentieth century filmmaking sometimes referred to as the ‘visual music movement’. Crucially, in the context of creating a film from the New Babylon models, the merging of images, colour and music, was intended to “impart mood”.

New Babylon continues to cast a sonic shadow in unexpected places,

including a recent ‘high concept’ fashion video for Adidas called New Babylon, with a soundtrack of abrasive abstract electronica – Input Vein by Kid Smpl – and a segment of Constant’s own text. In Amsterdam, sound artist Justin Bennett is working with students on a series of sonic events on the theme of New Babylon, partly based around the shopping centre with the same name in The Hague. More broadly, the Situationists have been cited as influences by alternative musicians and musical impresarios including Bowie, Malcolm McLaren and Factory Records’ Tony Wilson.

Rather than trying to ‘hear’ the sounds of New Babylon from the scant direct evidence that exists, a task made even more challenging by the contradictory nature of what little there is, it seems more realistic and productive to collate the various ways in which Constant’s urbanistic practice intersected with musical experimentation across a range of axes, from the avant-garde composing and free jazz scenes of Sixties Amsterdam, fellow artists who were themselves experimental musicians, film soundtracks and the ‘sound effects’, the tapes that accompanied his lectures and the reported experience of them, in Constant’s embracing of multiple media and synaesthesia, to his own musicality which, although ‘artisanal’ and folk-oriented, was often improvisatory. From these clues, certain features of a sonic imaginary for New Babylon suggest themselves.

It would almost certainly be a sound-collage, a mash-up; a mix of sound effects, film and library music, improvisation, jazz - composed and ‘free’, gypsy music, electronics, picked guitar, plucked violin and hammered cimbalom, ambient and field recordings, noise, musique concrete, bent-out-of-shape versions of classical compositions and official ‘state’ music [e.g. brass bands] plus random ‘field’ recordings of urban and social situations or events.

It would be overwhelmingly instrumental, perhaps to avoid the specific referentiality of lyrics and song-narrative. It would lean towards cacophony, atonality, dissonance, provisionality, incompleteness, rupture, senselessness. It would eschew completism, rationality, structure, harmony, lyricism, romanticism or repetition. It would never reach resolution, or end.

In addition to these sonic clues, some broader principles need to be factored in: specifically his intention that “art should awaken” and might need to disorient and disturb in order to achieve that aim; the belief he inherited from the Situationists, and the Lettrists before them, in the psychogeographic power of the urban form to determine states of consciousness; and his concomitant faith in the emancipatory potential of electronic technology to enable citizens to design their own urban environments and especially ambiences.

Project this vision forwards into the present day and one pictures the temporary spaces occupied by New Babylon’s permanent migrants, each with its own MPC, mixer and ambient speaker array, a universal digitised library of musics and sounds, a parallel set of resources to manipulate video, lighting effects and colour, and the software to interface all these into a synaesthetic, ever-evolving envelope. As Constant said of his city’s new model citizen; “In order that he may create his life, it is incumbent on him to create that world.”

– Steve Taylor

Related

The proposed plan for Shaftesbury Square formed part of the larger Belfast Urban Area Plan 1969, which was shelved due to The Troubles. We join forces with local resident Helena Hamilton to imagine an alternative universe where the Plan was built, and recreate it through sound.

PART 6: BELFAST SHAFTESBURY SQUARE

Helena Hamilton

In 1954, an alternative Central London was proposed by the planning giants Geoffrey Jellico, Ove Arup and Edward Mills. Seven decades later we are there with Mieko Shimizu to reimagine how that future may have sounded.

PART 5: LONDON SOHO

Mieko Shimizu

Kode9 takes a musical-imaginary glance at what could have been if Bruce's 1945 blueprint for a new central city had been built.

PART 4: GLASGOW BRUCE PLAN

Kode9

Nick Luscombe interviews Kode9 about his contribution to MSCTY_EXPO: REASONS TO BE CHEERFUL, focused on a musical reimagining of the 1945 Bruce Report for Glasgow.

The Erasure of Climate and People

KODE9 INTERVIEW

Felix Taylor explores the fine line between utopianism and dystopianism with Charles Glover's wonderfully ambitious 1930's plan for an airport over Kings Cross in London.

PART 3: LONDON KINGS CROSS AIRPORT

Felix Taylor

The writer and researcher Steve Taylor explores themes of unbuilt architecture connected to MSCTY EXPO: Reasons to be Cheerful Zone through explorations of Constant Nieuwenhuys' work.

Soundtrack for an Unbuilt City

STEVE TAYLOR

Ani Glass revisits the grand unbuilt plans for Cardiff's Centreplan 70.

PART 2: CARDIFF CENTREPLAN 70

Ani Glass

A sonic response by Forest Swords to C.H.R. Bailey's unbuilt 1960 design for Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral.

PART 1: LIVERPOOL METROPOLITAN CATHEDRAL

Forest Swords