MSCTY_EXPO Sound in time and step with architectural space

MSCTY_EXPO (LDF ZONE)

Sound In Time and Step with Architectural Space

Frozen Music

Goethe famously said that “Music is liquid architecture; architecture is frozen music”, and it is true that while architecture has a weight and materiality that is fixed to the earth and therefore static, it contains within it spatial rhythms, colours, geometries, textures, mathematical proportions, intervals and harmonies that align it closely to the discipline and perception of music. This symbiosis works equally for music; and at times, when perfectly matched, the bond between solid architecture and transient sound can become seamless: when the 13th-century polyphonic music of Pérotin was played in Notre Dame, for example, or a minimalist composition by Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alva Noto (“Glass”) was improvised in Philip Johnson’s Glass House in 2016, turning the architecture itself into a musical instrument. On occasions like this there is a confluence of materials, colours, space and sound that evokes a unique empathy between the two disciplines.

But Goethe’s statement, which itself reads like a mathematical equation or phrase in music (with symmetry and dissonance), denies two elements that are in fact intrinsic to architecture, or rather the experience and perception of architecture, and which bring it even closer to music: that is, movement and time. For like music, architecture is experienced through space – it is not only perceived from the outside, as a whole – and the movement of a person through this articulated space involves time. Moreover, the experience of architecture is inseparable to elements that are as fluid and transient as music itself, as Monet perceived when he painted Rouen Cathedral or as the 19th-century Japanese artist Hiroshige portrayed in his woodcuts: the dissolving of materials into sunlight or rain, the movements of light and shadow, the changes in colour and definition, depending on the weather and specific time of day. I would argue then that architecture is even closer to music than Goethe’s words suggest, and this is sometimes most evident in the forms of architectural expression that precede or imagine the built form or future city: sketches, ideas, concept models, abstract drawings – forms that also intersect with fine art.

This notion of movement and time as connecting and corresponding factors in architecture and music is explored in two of the collaborative projects in Musicity Expo 2020: “Theatrum Mundi” by architect Daniel Libeskind and “Meditations on Theatrum Mundi” by composer and multimedia artist Yuval Avital; and “The Horizon: your steps are a metronome. 30 minutes, 23 July 2020” by landscape and architectural designer Lily Jencks and “Return to the Horizon” by sound artist Hannah Peel.

Meditations on Daniel Libeskind's “Theatrum Mundi” [12 images]

← Click/Drag/Swipe →

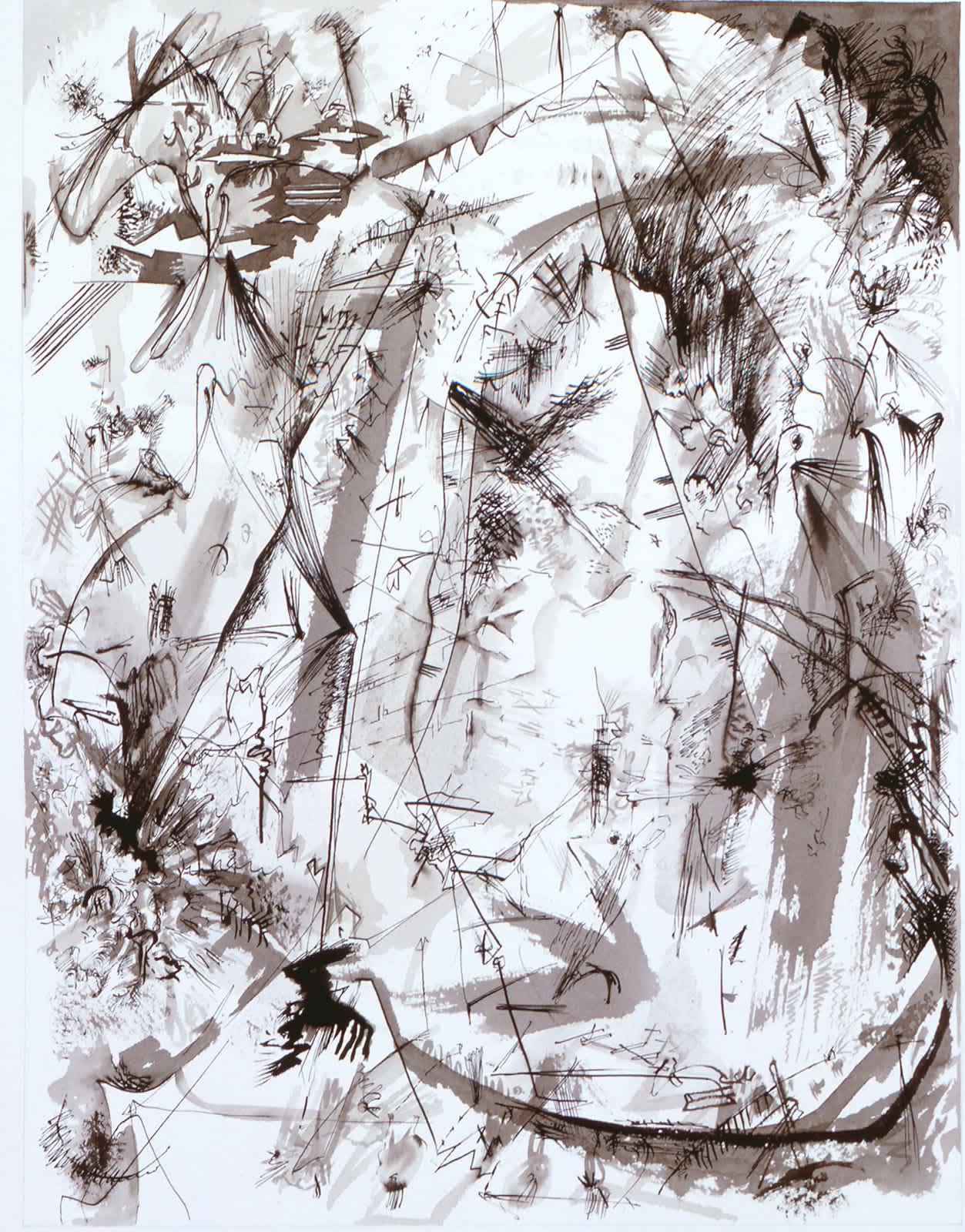

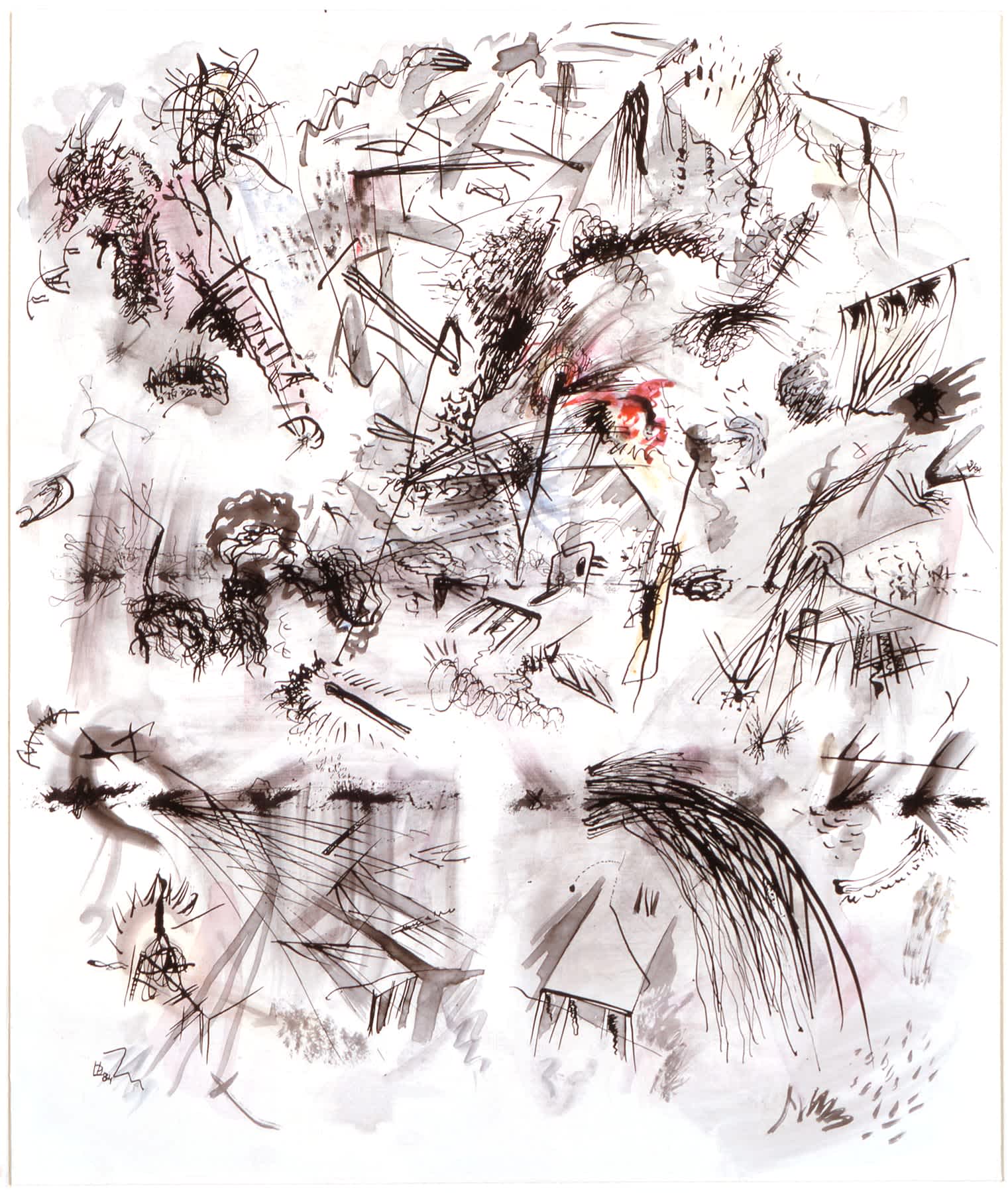

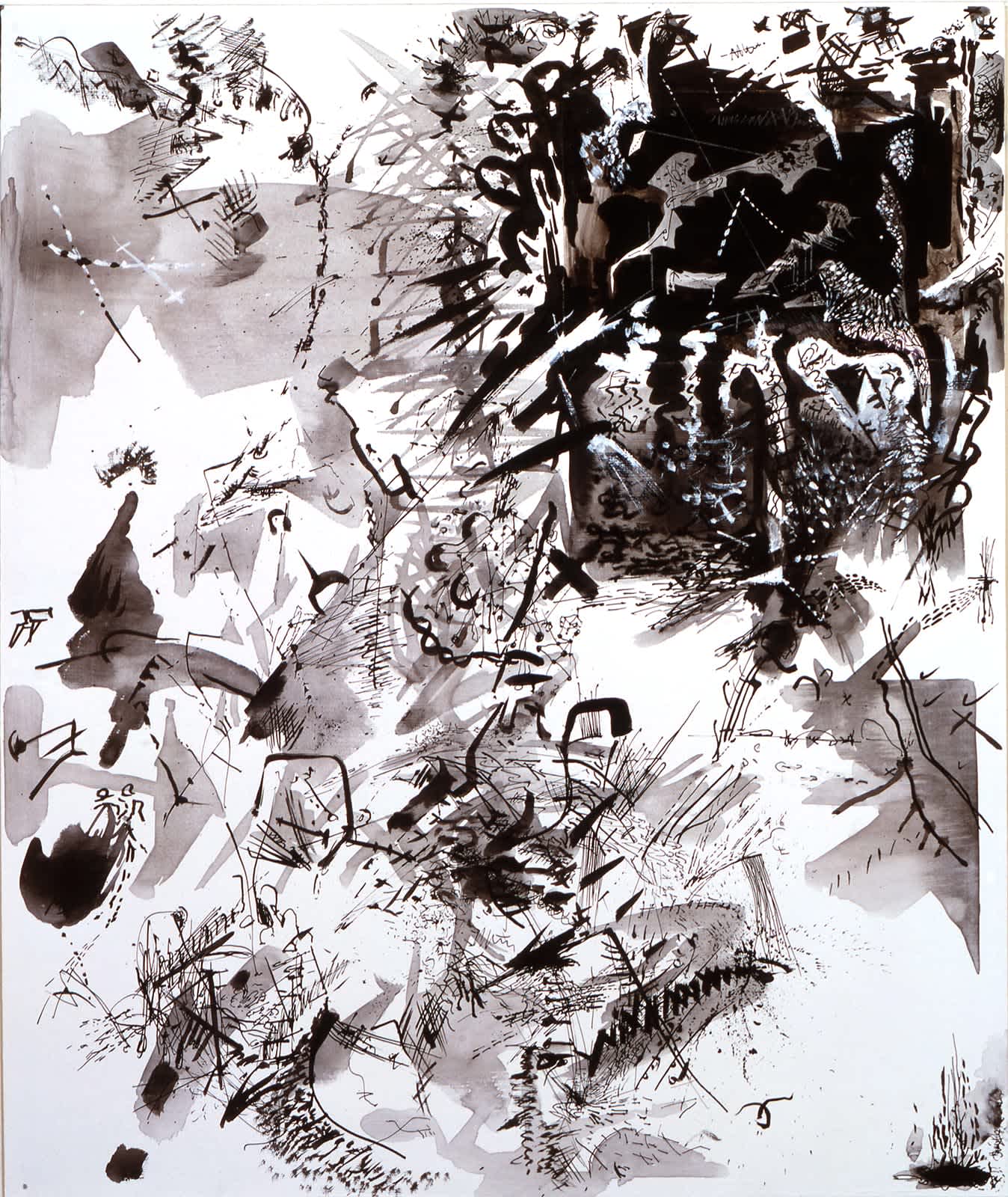

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Theatrum Mundi images and titles, 1983-5, © Studio Libeskind

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, 2020, © Yuval Avital

Libeskind + Avital

Libeskind’s “Theatrum Mundi” (the term given to the metaphorical concept of the world as a theatre, as developed in Western literature and philosophy) is a series of 12 abstract colour images, of drawings made by the architect in 1983 using paper, collage and paint on board. These original pieces were built into wooden boxes with operable doors for opening and closing, so with a structure that invited movement and interaction on the part of the viewer. A book was also made of the images in 1985, featuring a text by the architect, and published by the Architectural Association in London. Libeskind, who was born into the grey and still deeply anti-Semitic world of post-war Łódź in Poland (part of the Soviet Union) – the son of two Holocaust survivors – played the accordion from the age of six, describing his first impressions of the traditionally folk instrument, on which he would excel as a performer, as a secret “piano in a suitcase”. For Libeskind it was the “joy” of music, of weekly Yiddish Theatre and nightly radio that brought colour into his life.

In the book of “Theatrum Mundi” (now out of print), the plates are arranged in an accordion format to emphasise their circular relationship; and as images that move from a single colour palette of complex lines, geometric shapes and brushstrokes through a more textured layering of paint, collaged newspaper and notes of colour, with visual signs of architecture and cities, the viewer can almost “read” them in a musical sense, as a painting by Kandinsky or Paul Klee might be read; as a “score” with 12 sections that can operate in circular time. “Safe-guard entering” and “Reddish”, in particular, contain elements that resemble music notation, even the lines on a musical stave, as well as vertical structures that resemble columns and skyscrapers.

What makes these images seem so extraordinary and pertinent to 2020 is that Libeskind described them in his original text as “giving visual form to a premonition of the future in the form of a city besieged by an unknown infection”; and many of his titles now echo with unnerving familiarity: “Congregation”, “Safe-guard entering”, “Prison bound”, “Sadness”, “The threshold going out”. In a recorded video that he made for the sound artist, however, Libeskind explains that “Theatrum Mundi” is about more than a physical infection; it relates to the psychological and spiritual health of the city too: “… viruses that destroy the city’s very fabric, that resonate in the minds of people, as threats to civilisation itself. I did it [the drawings] by combining images of cities and new senses of direction, which tend to destroy the city’s moral and ethical fabric. This is a permanent quest. … Cities produce new phenomena, new ideas, new senses of being; they produce new worlds, not merely brave new worlds but also scared new worlds. … ‘Theatrum Mundi’ is about a world that is completely insignificant in every way when looked at from the perspective of the spirit of the city.”

Yuval Avital (born in Israel, now living in Milan) is a multimedia artist, composer and guitar soloist, working with sound in theatres and opera houses, and creating sound-sculptures, visual (“icon-sonic”) works and immersive sound-based installations in both art and non-art settings. He therefore seemed just the right artist to enter into a dialogue with “Theatrum Mundi”, and with an architect whose built works include the Jewish Museum Berlin (2001), the World Trade Center Masterplan (2003), the Extension to the Denver Art Museum (2006), and the Dresden Museum of Military History (2011).

Responding to the images and text first, before seeing Libeskind’s video (“a message in a bottle!”), Avital shared his impressions directly with the architect in New York in a one-hour zoom call on the 4th August, speaking from his studio in Milan. It was the first time the two had met. Having already worked intensely for three days to map out a first draft of 12 individual cyclical pieces to correspond to each image (which he had read “as both artwork and score”), Avital played his sound sketches to Libeskind, moving the images on the screen. To the composer and curators it felt like a very new form of collaboration: “creative space happening in virtual space”, he said.

Knowing Libeskind’s story, Avital described their first connection as being the accordion:

“I love the accordion and have written much for it, including 2 pieces for 7 accordions and one piece for 34 accordions. So I thought, “Why don’t I take these works and play a little with them here.” But later, when I listened to you speaking [in the video] Daniel, about the process in these images, I thought it was similar to what I am trying to do: ascendance and descendance. The city and its architecture are like harmony and composition, all trying to create an ideal order. But sometimes when this doesn’t work, it needs to break, to deconstruct in order to reveal a deeper, more important truth. The term theatrum mundi represents historically an idea of the world as a false stage that covers the truth within life. And I think that somehow in this Covid-19 moment, this crisis has given us a chance to open our eyes. I remember going to my studio in Milan and watching the eyes of the people that walked towards me, with their masks on, and something in their eyes was terrified. There was a feeling, a layer, of imminent danger. When I started reading the image titles for each scene, I became fully immersed in this theatrum mundi microcosmos and the elaborated sounds of the accordion for me became physical materials within it: rivers, shadows, sand, ruins, minds. Many of your works as an architect, Daniel, remind me of the gesture of the accordion’s bellow [opening in and out]: it is a sonic lung that is breathing.”

“That’s a beautiful thought,” Libeskind replied. “These drawings were made such a long time ago, that the thought for me too is in the images, and what you have now said is relevant because then, just as now, I believed that what we control is not the truth; it is not reliable. The reality is completely elsewhere, exactly in the realms that we are now exposed to. It is the piece of our mind that is not controllable and these elements penetrate through and into the drawings or paintings, between the gestures of making. It’s strange now, meeting up with these thoughts that were not really around at that time [in 1983-5] because then everything was getting brighter and progressing, everything was getting more and more consumed and optimistic; so these drawings were on the other side of the moon, the side that we don’t see at all.”

Following the zoom conversation, Avital returned to his composition, thinking further in terms of time and collage, using his three accordion pieces as “materia prima elements”, digitally elaborated and manipulated as “the artwork’s sonic grammar”, with tiers of electronic sound and voice. He also felt it was right (in agreement with Libeskind) to animate the images, so that the viewer can “read” them as he has done, in a way that corresponds to the 12 compositions; for the viewing of art and architecture is not static, but mobile and directional, even in a subtle sense.

The results are almost cinematic: layers of sound, like messages in Morse code, travelling through space and time in all directions, occasionally tuning into an accordion melody, but only momentarily. The sounds vary from rhythmic pulsing and throbbing, like a radio searching for a connection, to deep accordion base notes that communicate fear and danger. The music is unsettling, with only occasional glimpses of something ordered and recognisable, like notes of birdsong or a fragment of fairground music. Composed through a series of drafts, beginning with an intuitive response and then with more detailed workings, additions and structures, there is a sense for the viewer who is also the listener of not being in control: a search for resolution and order that finds only seconds of hope. The accordion is perfect too for this theatrum mundi: an instrument that stems from lonely street corners and the network of dark alleys or courtyards in a city, its colour palette moving from black and white through to isolated reds, or yellows, blues, oranges and pinks. Avital does not expect the viewer to necessarily listen from beginning to end: like a building, it is possible to move through it in different ways each time; to meditate on its parts or as a whole; and to revisit.

Jencks + Peel

The idea of movement and time as connected to the city and sound is also highlighted in a new and specially commissioned artwork for Musicity Expo by landscape and architectural designer Lily Jencks, who is collaborating with experimental artist, composer, producer and broadcaster Hannah Peel, whose work includes soundtracks for film and television. Following their first conversation, and before knowing how Hannah Peel would respond, it was interesting to consider Jencks’ concept and how she had approached this interdisciplinary project. In contrast to the “Theatrum Mundi” and “Meditations” project, which is in a sense a time-traveller through decades, Jencks has placed her work, named “The Horizon: your steps are a metronome. 30 minutes, 23 July 2020”, in a very precise and narrow section of time, documenting a specific action, date and place: a walk across Chelsea Bridge in London. “I always think of architecture in terms of steps and choreography,” she says in our first discussion, citing the work of American landscape architect Lawrence Halprin as an influence. Halprin, who created a landscape garden for his own Californian residence in 1953-4, featuring an outdoor “dance deck” for his wife Anna, a choreographer and dance teacher, believed in the social impact of landscape architecture in the city, reshaping and improving people’s lives. The dance deck, which for the Halprins was a “landscape score” signifying a new approach to movement and collective dance, became synonymous with interdisciplinary collaboration, bringing together visual artists, composers, architects, poets, filmmakers and dancers, including Merce Cunningham and John Cage.

Jencks has likewise conceived of “The Horizon” as a score, but situated in the city. A long vertical artwork, or drawing of a single street as she calls it, composed of the river, bridge and street elevations on both sides, the online viewer sees it first as an abstract image, before zooming in (which is essential) to different areas and details, like sections or bars of music. Scrolling down and visually “entering” the piece, it is possible to read Jencks’ text, which moves with a kind of physicality in time with her steps, “walking in a clockwise direction”, documented through photography – one photograph taken every 10 steps. In this way the “30 minutes” in her title, which has echoes of Cage, is a record of both movement and time: the sections of the River Thames reading like the keys on a piano.

Jencks also references American artist Edward Ruscha’s “Every Building on the Sunset Strip” (1966) as an inspiration for the piece: his use of photography as a form of map-making and topographical study – “a model”, as MoMA describes, “of ‘one thing after another’ Minimalism as well as a ready-made chance arrangement”. To the vertical minimalist strip or map, however, Jencks adds her own poetic text, and marks like choreographic signs. The words are also spoken in her own voice in an accompanying video, against a background noise of wind and traffic. It was important, she said, for the sound artist to have a record of this. Inserted too are vertical, swirling wave-patterns derived from weather data, giving “The Horizon” a socio-political narrative relating to climate change in cities, as well as a very personal one. The patterns also suggest sound waves or music, like an invitation to respond in that other discipline. “I have always walked,” she says, “as a kind of musical meditation.”

As a landscape and architectural designer – co-founder of JencksSquared – with strong interdisciplinary interests, whose work includes Ruin’s Studio, a choreographed live/work/contemplation space in Dumfries, Scotland, and Maggie’s Centre gardens in Hong Kong and Glasgow, Jencks looks at the nature in a city as something that is often “unseen” in the “narrow streets (the muttering retreats)”, like the brown-grey reflective, rhythmic presence of the Thames, or the movement of clouds that are marking time; and she continues this theme of not seeing, which connects so closely to music: “I was interested to see if I could capture the specificity of an experience (in time) but also an abstraction, or generalities of a place; it is both poetically atmospheric and a precise recording of a particular duration. It is a way of reading the experience of the city without being able to see the city at all.”

Hannah Peel’s sonic response, “Return to the Horizon” (which echoes a line of text in the drawing), also has something strongly cinematic about it, perhaps because it was written in direct answer to Jencks’ still and moving images, to a specific location, and to spoken words in relation to that site. But even in isolation the music is atmospheric, full of movement and also stillness, with surges of electronic sound that capture the spirit of Jencks’ brown “amorphous” Thames in counterpoint to the “solid profiles” of buildings. When the voice comes through this sound, like a light entering a space, it seems connected both to personal experience and to something ancient, suggestive of Celtic origins; a traveller, like the river itself (“burier of secrets”), bringing messages from the sea; or the wind or clouds, with cyclical movements and a minimalist beauty, marking time. It is easy to picture the choreography that Jencks speaks of, even to imagine dance (which is a tempting thought for a curator); and above all, the feeling is of nature being a constant and prophetic presence in the urban environment; one that we must listen to, now more than ever. Like Jencks’ poetry and drawing, the sound is meditative, poignant and quietly beautiful.

It is also a fitting place – for it is certainly a “place” in the mind and senses that is conjured through these collaborations – to further reflect on the links between architecture and music, both now and in the future, through the image and metaphor of a bridge within a city.

Clare Farrow is a writer and curator, founder of Clare Farrow Studio @clarefarrowstudio

Related

Imaginary Sonic Visions by Bill Fontana is a sonic response to Enrique Sobejano and Fuensanta Nieto’s unrealised design for NCCA Moscow: New National Center for Contemporary Arts in Moscow – Competition Finalist.

IMAGINARY SONIC VISIONS

Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos

w/ Bill Fontana

Hannah Peel created her track by following the flow of Lily Jencks’ drawing. (The Horizon: your steps are a metronome. 30 minutes, 23 July 2020.)

THE HORIZON: YOUR STEPS ARE A METRONOME.

30 MINUTES, 23 JULY 2020.

LILY JENCKS w/ HANNAH PEEL

Yuri Suzuki re-imagines Richard Roger’s Zip-Up House as a musical instrument created via acoustic simulation of the space.

ZIP-UP HOUSE

Richard Rogers

w/ Yuri Suzuki

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, is a sonic response in 12 movements by Yuval Avital to Daniel Libeskind’s “Theatrum Mundi”, 1983, a series of 12 abstract works (paper, collage and paint on board) that give visual form to a premonition of the future as a city besieged by an unknown infection. The composition interprets the visual artworks as ‘mandalas’ and their titles as poetic vectors.

THEATRUM MUNDI

DANIEL LIBESKIND

w/ YUVAL AVITAL

Akrafokonmu/Soul washer's badge was written, performed and produced by Chisara Agor in response to Elsie Owusu's A Gallery for Returning Treasures.

A GALLERY FOR RETURNING TREASURES

ELSIE OWUSU

w/ CHISARA AGOR

Essay

Back to the Future: Revisiting the World Expo

by Rebecca Morrill + Guy Tindale

PiM.studio Architects, A music hall in the Alps, Valsolda, Italy, 2019 – competition

ARCHITECTURE MEETING NATURE MEETING SOUND

PiM.studio

w/ mcconville

Essay

Sound In Time and Step with Architectural Space

by Clare Farrow

Loraine James presents a visionary sci-fi dreamscape for Ab Roger’s cocoon-like structures.

LIVING WITH BUILDINGS

AB ROGERS

w/ LORAINE JAMES