sa-x and the city

REEL 2 REAL

In Praise of the Tape

In summer 2017, in the window of a record shop in Edinburgh’s Old Town, a hand-written sign announced simply ‘Tapes!!!’. The three exclamation marks caught my eye, suggesting the writer was rather surprised to be selling them again.

This was a format that was seemingly dormant, if not almost entirely defunct, through the eras of CDs, mini-discs, MP3s and online streaming. While the so-called ‘vinyl revival’ is widely-known and flourishing [in 2016, vinyl album sales outstripped digital downloads], and indeed true vinyl aficionados would argue they never gave up on buying records, it’s harder to find such evangelists for the humble and unfashionable cassette tape. Perhaps with good reason. Audiophiles criticise its poorer audio quality compared to vinyl or digital formats: there’s a loss of breadth and depth to recordings, caused by the compression required to squash all that data onto those thin ferric oxide-coated magnetic strips of tape. And for the rest of us, your average music listener, we simply became frustrated with cassettes for other reasons: their tendency to get mangled in the player, or to stretch and distort with overuse. And then there was the fact that unlike vinyl, where the needle could be placed on the record at any point on the recording to instantly hear a specific part, and CDs, where tracks can be skipped through at the touch of a button, the cassette tape required endless rewinding or fast-forwarding to find that magic song that you want to hear over and over.

Click – stop – click – rewind – click – play.

It’s no wonder we abandoned tapes without a second thought when offered a superior new format. So, why would anyone go back there now? Technology has surely moved on and made the cassette obsolete. I mean, who tries to light a fire by rubbing two sticks together when they’ve got a box of matches?

Yet the cassette tape has another side [one might call it the ‘B’ side] to its history and function, which makes it a more revolutionary format than many might realise, namely recordability and portability.

The fact domestic users could record onto tapes opened up a world of possibility for wannabe DJs or anyone who wanted to compile their own mixes: all thriller, no filler. The creation of a mixtape was, for those of us of a certain generation at least, a rite-of-passage experience. We made them not only for ourselves, but also for friends, lovers, or anyone we wanted to impress with both our musical good taste and our ability to ‘curate’ the selection so that it flowed meaningfully from track to track [albeit no one would ever have called it ‘curating’ back then.]

Compiling the perfect mixtape was a skill to be honed through practice. Not only did you have to think about which tunes you wanted to include, you also had to consider the physical means by which you would transfer music – whether it was recording them direct from the radio [finger hovering above the record and stop buttons to avoid getting the interruptions of the presenter’s voice]; or from vinyl – if you were lucky enough to have a combination record/cassette player [otherwise you sat your tape recorder right next to the record player, told everyone around to be quiet and hoped for no passing ambulance sirens]; or tape-to-tape, once double-deck machines became affordable and reached the mass market. And then there was the mathematics of it all: trying to make the most effective use of the fixed length of tape – how many songs could you get onto each 45-minute side of your TDK S-AX C90? And what was the best division between A and B side to avoid that long stretch of blank tape at the end of one side, or worse, a song being cut off part-way through because the side had run out too soon. Creating the perfect mixtape was easily a whole afternoon’s work, but oh! the bliss when you knew you’d nailed it. That tape would be played on auto-reverse for weeks and months to come.

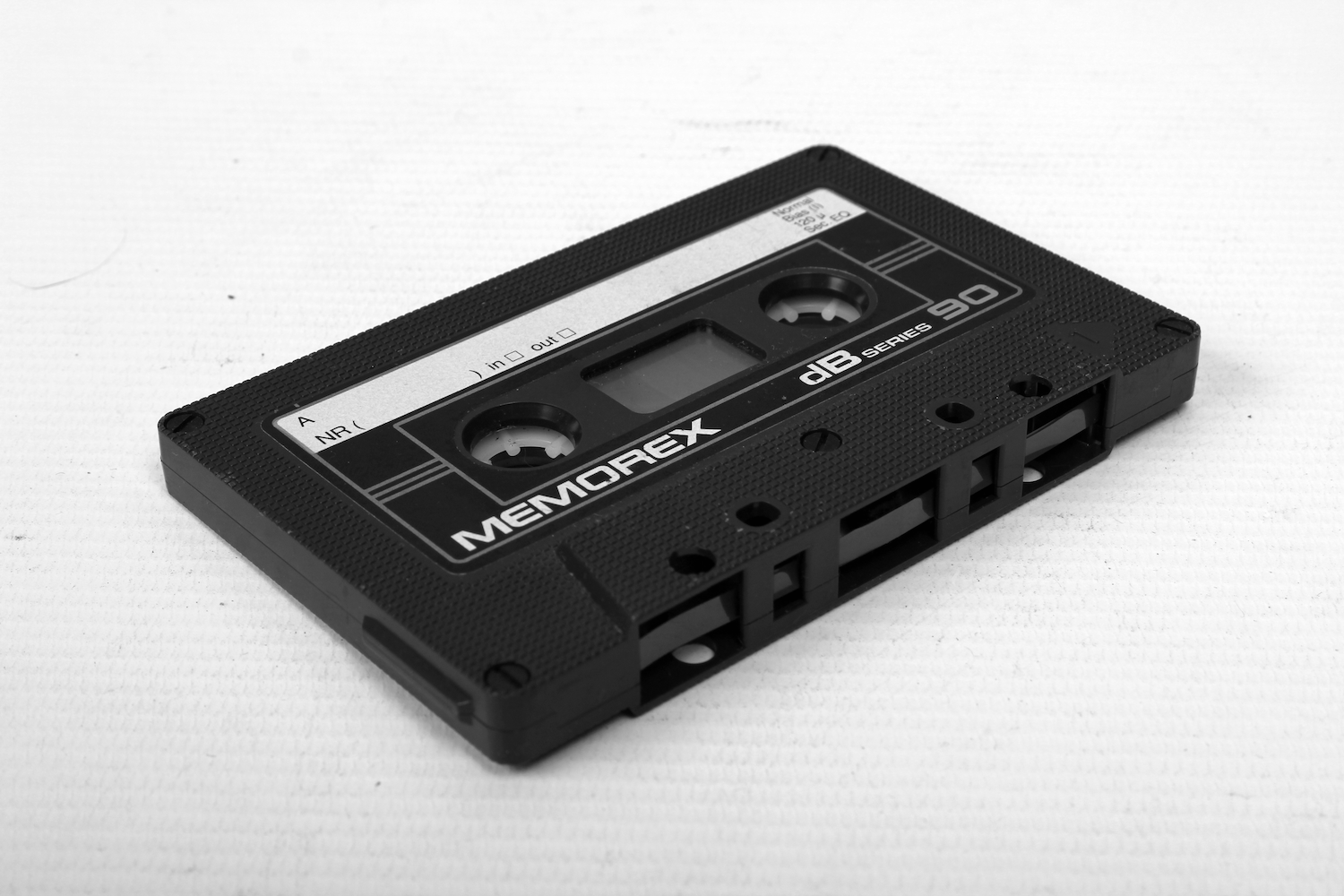

The Memorex dB-90.

Original link.

Recordability wasn’t just for music. When I got my first cassette player, on my 10th birthday, it came with an in-built microphone. I also received a triple pack of blank Memorex dB-90 tapes, which was as exciting to me as a new sketchbook and fresh set of felt tip pens: just so many creative possibilities. Peeling off the cellophane wrapper, carefully sticking the blank name label onto this virgin rectangle of plastic [make sure it’s not wonky – you’ll never get it off in one piece], and turning the cardboard insert of the plastic box the other way around, ready for the track-listings to be neatly transcribed in pencil, became nothing short of a ritual. Despite knowing I could re-record on these tapes many times over before I wore them out, the first recording onto a pristine tape always held a special delight. No glitches, no ghost sounds from previous recordings, all pure and clean.

So what did I record? Well, for reasons that I don’t recall, I went around the house with my low-rent ghetto-blaster and captured as many household noises as I could find. From a running tap, to a slamming door, to my mother’s industrial sewing machine at full speed, to the inimitable [and endlessly amusing] fart of a balloon deflating and flying around a room. The recordable cassette offered a way to capture the overlooked, everyday soundscape of the world around and compose them into what I now realise, was a kind of avant-garde sonic mix. I also unwittingly caught a snippet of my grandmother talking in the background [an annoyance at the time – didn’t she know she was ‘on air’?], but when I came across this tape again recently, over 20 years after she died, I realised this might be the only recording anyone had of her voice.

Nostalgia, memory and emotion are an intrinsic part of our relationship to music and sound, and this also connects with the other key aspect of the tape: portability. While no doubt, the first generation of the phonograph and gramophone were equally and justifiably bowled over by the fact that they could now listen to their favourite music and performers whenever they wanted, in their own homes, the playback equipment wasn’t exactly pocket-sized: the archetypal gramophone player being larger than your average Jack Russell dog. Furthermore, vinyl records were prone to become damaged or scratched if moved while being played. Even dancing too enthusiastically in the living room [to Kate Bush, c.1978] could bounce the needle and provoke one’s father’s wrath.

All that changed with the cassette tape. Lightweight, robust and as small as a box of cigarettes, tapes were asking to be carried around. If you’d rushed to the nearest record shop [Woolworths] on a Monday lunchtime to pick up a new album on the first day of release, you could slip it in your jacket pocket and easily whip it out beneath the desk to impress your schoolmates at afternoon registration before you’d even listened to it. Perhaps it wasn’t surprising when, in 1979, a leading Japanese electronics company launched a tape player that also fitted in your pocket – the Sony Walkman. Many imitators quickly followed and the ‘personal stereo cassette player’ soon became an essential piece of kit for music lovers everywhere and paradise for introverts [‘I have headphones on… don’t talk to me’]. We could have music wherever we went, no toe bells required. And no more arguments on long car journeys about who wanted to listen to what, each passenger could plug themselves into their own preferred soundtrack, enjoying their favourite tunes while they watched the landscape whizz by.

The oft overlooked effect of listening to music on the move is that particular tracks become connected with particular places. In the same way that smell has a powerful effect in triggering specific memories [for me, the scent of fresh mint will always take me straight back to summer holidays in my great aunts’ garden in Devon], so music can become embedded in our minds in connection with specific places and buildings. Of course, our brains use all five senses to gather data on everything we see, hear, smell, taste and touch. Yet music – with its variable sounds and pitches, its repeating rhythms and pattern of beats, its lyrics too – has a unique superpower, beyond any other kind of sounds we hear, to fix itself rigidly in our memories. It’s why we can recognise a song we haven’t listened to since childhood after just two notes. It’s why the concept of the ‘earworm’ exists. It’s why someone heard the sound of the ticket barriers on the Jubilee Line at Canary Wharf underground station, and immediately thought of Blur’s ‘Song 2’ [it’s gained almost million views on YouTube]. Combined with the ever-changing visuals we take in when we’re out and about, particularly within the city, the equation of music + place = a powerful combination in the laying down of memories. And the cassette’s role in the history of this phenomenon, due to its innate portability, is surely something to be acknowledged and celebrated.

So while I’m not about to give up streaming tracks on Spotify from my iPhone while I’m on the move, nor about to go back to my Walkman, the endless purchases of AA batteries and a rucksack perpetually cluttered with tape boxes, I will continue to hold a fondness for my library of cassettes. While detractors might be disdainful, arguing that this is just the latest hipster trend – backwards-looking nostalgia, repackaged and sold back to us at a premium by millennials – I don’t believe it ought to be so quickly dismissed. Furthermore, I personally rather like the unique audio qualities of a cassette tape. The gentle hiss of the leader tape before the music starts, the whir of the revolving cogs that turn the pair of plastic sprockets. It’s the authentic sonic signature of an analogue format, like the crackles of the needle on a vinyl record. Once something to be eradicated in the pursuit of purity, now something to cherish as a tangible object in an increasingly digitised world. Viva cassette tapes! A revolutionary format.

– Rebecca Morrill, 2017

Related

Low Line reflections from Sam Mackay

Contagious Where the Visual is Not

SAM MACKAY

Richard Foster explores his own sonic experiences of the great Baltic city of Tallinn.

The Doors Themselves Are Remarkable!

RICHARD FOSTER

Architect + sound artist Paul Bavister [Flanagan Lawrence, Bartlett School of Architecture] explains the processes involved in making acoustic measurements of spaces for site-specific creative responses.

A Creative Springboard for Music

PAUL BAVISTER

Insights into the processes involved in creating a site-specific musical response to one of the City of London's contemporary icons.

Sounds of the City: Interview

NICK LUSCOMBE w/ MIDORI KOMACHI

SA-X + The City

REBECCA MORRILL

London Design Biennale 2021's Japan Pavilion sees MSCTY_Studio recordings interpreted as "Reinventing Texture”, which links London + Tokyo through a multi-sensory tribute to Japanese Washi paper-making and papier-mâché.

MSCTY_Studio w/ Toshiki Hirano + Clare Farrow

REINVENTING TEXTURE