Back to the Future: Revisiting the World Expo

MSCTY_EXPO (LDF ZONE)

Back to the Future: Revisiting the world expo

Essay by Rebecca Morrill + Guy Tindale

Before smartphones placed more information than we could consume in a lifetime at our fingertips, before the Internet distributed images around the world in an instant, before the growth in budget aviation made global travel a mass experience, in the distant past of a few decades ago, one of the best ways to experience the world’s rich variety in one location was to visit a World Expo.

Also known as World’s Fairs, these exhibitions were held every few years in different host cities. Countries and large corporations showcased their latest cultural and technological innovations in specially designed pavilions.

The first World Expo that was titled as such was held in Montreal, Canada. Photographs and film footage of Expo ’67 reveal in vibrant colour the futuristic vision for which Expos were best known. One of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes, realised on a colossal scale, served as the United States pavilion. Frei Otto’s floating tensile peaks represented West Germany, while a technicolour Kaleidoscope pavilion was filled with R. Murray Schafer’s avant-garde music. ‘Habitat’, an ambitious essay in affordable mass-produced social housing, still stands as one of the few surviving structures of this Expo, an emblem of Montreal and, ironically, an extremely expensive place to live. The whole architectural wonderland was connected by a driverless ‘Minirail’ that snaked throughout the 1000-acre site and transported many of the 55 million visitors who experienced Expo ’67 during its six-month run.

General View of the Interior (from Recollections of the Great Exhibition), John Absolon, 1851 Original link

Exposition Universelle

The Exposition Universelle ('Universal Exhibition’), from which the Expo derived its name and purpose, goes considerably further back in time. The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, held in London in 1851, is commonly considered the first such exhibition. It was itself a response to The Exhibition of Products of French Industry, held in Paris eleven times from 1798 to 1849, where the achievements of post-revolutionary France and the resources of its growing colonial empire were on display. The London exhibition aimed to offer a more international perspective, presenting exhibitors from Britain and its ‘Colonies and Dependencies’ alongside 44 foreign states from Europe and the Americas. Housing the exhibition was its centrepiece, the Crystal Palace. Joseph Paxton’s enormous modular structure of cast iron and 294,000 panes of plate glass was constructed in just eight months in London’s Hyde Park and represented an architectural revolution.

While the Great Exhibition undoubtedly sought to prove Britain’s industrial and technological superiority on a world stage, is nevertheless still held up as landmark in the history of the International Exhibition, and was soon replicated in other cities including Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876), Melbourne (1880), Barcelona (1888), Brussels (1897), St. Louis (1904), Milan (1906) and San Francisco (1915). In Paris, the Exposition Universelle soon followed suit, shifting from a national to international focus. Its 1867 edition presented over 50,000 exhibitors, of whom only 15,000 came from France and her colonies. This was the first time that Japan, newly opened-up to the outside world, had a presence and the art shown proved hugely influential on Van Gogh and other post-Impressionists artists, who went on to integrate its aesthetic into their own work. Innovations on display included reinforced concrete, elevators, and the telegraph, all of which would radically reshape the urban world in decades to come. The next Paris exhibition, held in 1889 to mark the centenary of the French Revolution, included the tallest structure in the world at the time. It was ascended by almost two million people during the run of the exhibition – this iron tower of three hundred metres constructed by the firm of Gustave Eiffel.

After a hiatus forced by the First World War and its aftermath, an intergovernmental organisation, the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE), was created in 1928 to oversee the selection, regulation and organization of international exhibitions. Between the wars these were hosted by Barcelona (1929) – site of Mies van der Rohe’s celebrated pavilion – Chicago (1933), Brussels (1935) and Paris (1937). In 1936, a new strand of smaller-scale ‘Specialised Expos’ was launched, the first, in Stockholm, having the theme of ‘aviation’. This was followed by further exhibitions focused on water, housing, sport, energy and later by even more niche subjects such as ‘citrus fruits’ (Beit Dagan, Israel, 1956) and the ‘Reconstruction of the Hansa District’ (Berlin, 1957).

Over time, the overarching themes of the larger World Expos shifted from an emphasis on the values associated with industrialization and colonialism to an agenda of cultural exchange, starting in 1939 with New York’s Building The World of Tomorrow, and continuing with The Festival of Peace in Port-au-Prince, Haiti in 1949 and A World View: A New Humanism in Brussels in 1958. Two more North American Expos followed, in Seattle in 1962 and New York in 1964, which took the themes of Man in the Space Age and Peace Through Understanding respectively. These left two architectural icons: the Space Needle in Seattle and Unisphere in Queens, New York.

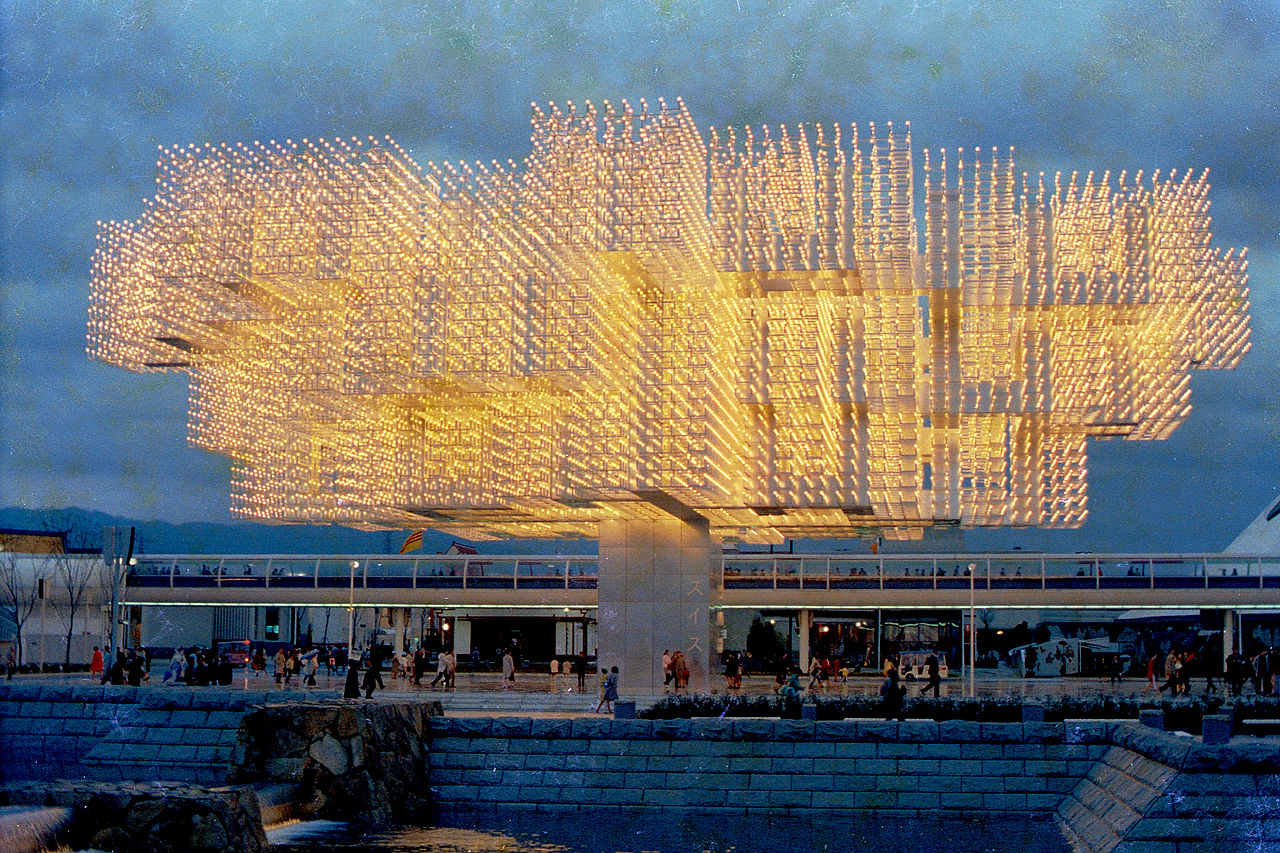

Switzerland Pavilion, Osaka Expo'70. April 1970. Original link.

Osaka'70

In 1970, the first World Expo to be staged in Asia – indeed the first to be held outside of Europe and North America – was presented in Osaka, Japan. Expo ’70 has been seen by many as the zenith of the golden age of International Exhibitions. Lasting from March to September, it was the largest to date, with 77 national pavilions and a number of corporate pavilions expressing architectural innovation on the grandest scale. Modular construction was, as ever, key to rapid construction, but this time expressed in strange organic forms and inflatable structures as well as now-familiar geodesic domes or the gigantic box – the world’s largest ‘space frame’ building, the ‘Big Roof’ – at the heart of the Expo. This time, suspended monorail cars offered a glimpse of future public transport, carrying up to 64 million visitors around the central ‘Symbol Zone’ and the ‘amusement riding facilities’ of nearby ‘Expo Land’, all presented on an 8,000sqm site (chosen to represent 1/10 millionth the area of Japan).

As with the Montreal Expo three years earlier, the Osaka exhibition presented an idealistic vision and, according to curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, ‘the realisation of a techno-utopia’, albeit only temporarily. However, it also signified Japan’s return to global prominence after the devastation of World War II, demonstrating how the country had been miraculously rebuilt – physically, economically and morally – to achieve the second largest gross national product after the United States. The overall theme of this Expo, Progress and Harmony for Mankind, spoke of spiritual as well as technical advancement for peaceable purposes, and for the benefit of all people. In some ways this new world had just materialised, with the first Moon landing a few months earlier: spacecraft had pride of place in both the US and Soviet pavilions, and the Americans offered the public a first chance to see a large chunk of moon rock brought back by the crew of Apollo 12. But the Space Race was more an expression of international competition than cooperation, and the hopes of Expo ’70 were seen, even at the time, in a context shaped by the Vietnam War, student protest, civil unrest and political violence. A worsening economic climate that would end the Apollo project just two years later would turn into a full-scale crisis after the 1973 Oil Shock, rendering obsolete the airy but energy-intensive urban visions presented in Osaka.

At the centre of Expo ’70 were two contrasting architectural visions, both distinctively Japanese. Much of it came from the Metabolist movement, whose 1960 manifesto conceived buildings as living systems. Metabolism was a fusion of the grand modernist schemes of Le Corbusier with indigenous principles of harmony and balance with nature: hi-tech meets folklore, an aesthetic familiar now in anime culture. In terms of design, it took modular construction to its limits, with functional spaces that could be plugged-in and moved at will. Connecting geometric and biomorphic forms was the concept of the living building, not merely containing space but adaptive and channelling information. Its principal exponent, Kenzo Tange, co-designed the overall Expo site and especially the ‘Symbol Zone’ – the Central Plaza and the Big Roof. Echoing Paxton’s Palace of 1851, this was conceived as a social space, with visitors and performers rather than exhibits taking centre stage. Piercing the roof was artist Taro Okamoto’s mysterious Tower of the Sun, one of the few elements of Expo ’70 still standing today. Metabolism had grown from the utter devastation of post-war Japan, but with that seen as an opportunity for rebirth rather than simply a loss to be restored. Also representing this movement at the were the startling hovering fountains by Isamu Noguchi, modular housing by works by Kisho Kurakawa and the multivalent ‘Expo Tower’ of Kiyonore Kikutake.

Also on the Expo site was another, more disruptive vision, that of Arata Isozaki. A protégé of Tange, but opposed to Metabolism, he built two colossal ‘robots’, which were, in fact, ‘buildings in disguise’ that transformed into performance spaces. Despite their overtly mechanistic appearance, Isozaki’s structures embodied chance, randomness and responsiveness to people, principals that the architect believed were missing from the rigorous planning of Metabolism.

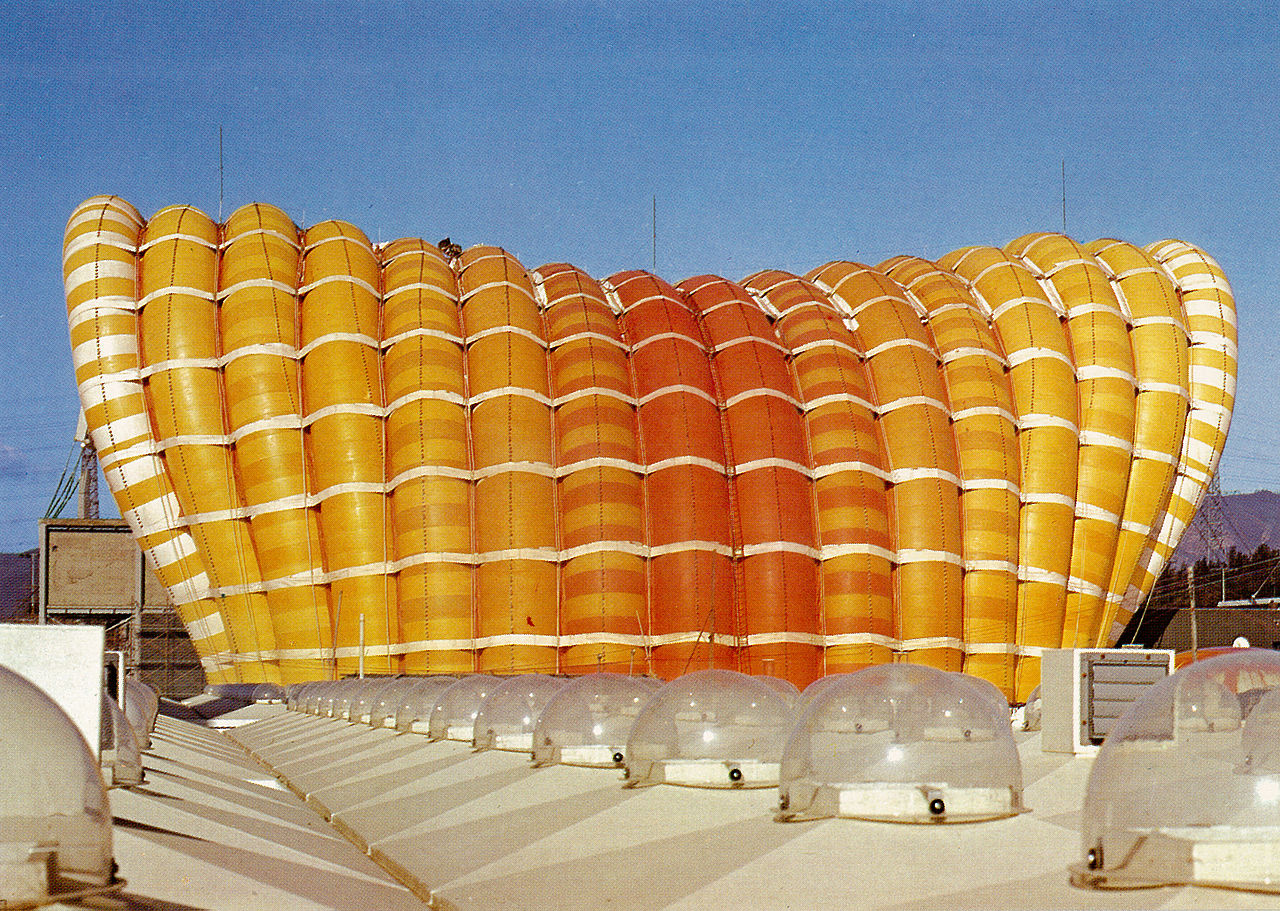

The Fuji Pavilion

Fuji Pavilion, Osaka Expo'70, Original link

The Osaka Expo also featured ambitious corporate pavilions: the inflatable Fuji Group Pavilion in which the world’s first IMAX film was shown; the Pepsi Pavilion designed and activated by Media Art pioneers E.A.T (Experiments in Art and Technology) and surrounded by a Fujiko Nakaya fog sculpture; and The Mitsubishi Miraikan (Future Pavilion) – a building loosely based on Hokusai’s The Great Wave, which presented a vision of the future in which weather control had been achieved, a reminder that Japan exemplified resilience not only against the disasters of war but also against natural calamities. The pavilion featured new technologies such as a smoke screen for projections, an innovation that has not found a place unlike some of the other hi-tech gadgets – lasers, local area networks and even primitive mobile phones – that were featured elsewhere at the Expo.

As with other World Expos, each participating country built its own temporary pavilion to showcase its national achievements. Japan’s was a collaboration between Kurokawa and the British avant-garde group Archigram, whose fantastical and, up to that point, unrealised architectural designs were here given solid form. This phantasmagoria featured interactive elements in a ‘peepshow’ that pointed to a consumerist future of generated desire. Uncompromising by contrast was the tallest pavilion, a soaring red canopy, which was to be the Soviet Union’s last appearance (it had ceased to exist by the time of the next Expo in 1992). Australia’s pavilion featured a large domed roof, suspended from a gigantic steel hook – a confident statement from a young nation turning its gaze towards East Asia.

Music

Music was an integral element of the exhibition, growing out of a Japanese avant garde that had been fostered by the national broadcaster NHK during the 1960s. Musicologist Emmanuelle Loubet describes how novel computer control and acoustic design were key to the spatial conception of sound pieces, according with the overall philosophy of responsiveness to architecture and environment. Joji Yuasa composed the multimedia piece Music for Space Projection for the Textile pavilion and Sound Curtain for the Communications pavilion. Six further pavilions were the setting for the environmental music compositions of Toshi Ichiyanagi.

There was an international presence to the music programming too. Fritz Bornemann’s pavilion for West Germany, the ‘Garden of Music’, hosted live performances of Bach, Beethoven and, memorably, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Expo, a composition for three short-wave radios. The pavilion’s subterranean displays and unique spherical auditorium became a favourite attraction for many visitors looking for a peaceful oasis within the sensory overload of the Expo. The Scandinavian pavilion contained the sound installation Poly-Poly, the work of composer Arne Nordheim and dedicated to John Cage. This durational work explicitly addressed the future, though in a way that was not completely realised during the Expo. Six looped tapes of different lengths simultaneously played electroacoustic material in a randomized but exhaustive sequence that would take 102 years to return to its beginning.

The new sound-world of electronic music also included more popular works. Wendy Carlos’s Switched on Bach, a commercial hit two years previously, provided a soundtrack to the United States pavilion. Carlos, and her collaborator Robert Moog, had inspired the 37-year-old Japanese film composer, Isao Tomita, whose turn to electronic arrangements made him an international star and Grammy winner in the 1970s; at Expo ‘70 he collaborated with jazz drummer Akira Ishikawa and his group to compose Sounds for Global Vision for the Toshiba pavilion.

The Central Plaza provided a venue where each nation had a chance to stage live concerts during its six months, some recordings of which still exist. It was also the setting for an ambitious live electronic performance, Fantasy of Sound and Light by Toshiro Mayazumi, involving screens and 11 channels to 1000 loudspeakers. Takehisa Kosugi, a composer greatly influenced by the Fluxus movement, performed three ambient pieces in the plaza, as well as the incidental music for Isozaki’s robots. One work was a montage of sounds from all over the world. Another was an early iteration of his groundbreaking piece, Catch Wave, where two inaudible high-frequency sounds, one projected from a speaker on a fishing rod, combined to produce varying audible tones. Meanwhile, the Japanese Steel Industry pavilion presented a ‘Concert Hall of the Future’ in which live music would be a thing of the past, offering instead definitive playback of compositions by Iannis Xenakis, Yuji Takehashi and the pavilion’s producer, Toru Takemitsu, via 112 channel sound over 1300 speakers.

In many ways, Expo ’70 was the last event of its kind to convey the idea of utopian possibilities, filled with strangeness and wonder. The next such event was held in Seville in 1992, at the post-Communist moment that asserted a hubristic ‘End of History’ rather considering a future of continual human progress. While equally grand, Seville adopted a different tone that now seems far more outdated than Osaka’s. Looking back to 1492, it was a celebration of ‘The Age of Discovery’, valorising the colonialism that was the most problematic aspect of earlier Expositions Universelles. Expos have continued more regularly since, with new concerns of ecology, urbanism, and food supply, however all have been criticized for their bombast, expense and unsustainability. Perhaps we need to turn back to the way the future looked in the past to find a vision needed for our times.

Loved even by those who didn’t attend it, including some fans who weren’t even born in 1970, the briefly-realised utopia of Osaka suggests an exuberant innocence, a world momentarily free from cynicism. One such enthusiast is German art-critic Claus Richter, writing under the soubriquet of ‘Doc Emmett’, who suggests that ‘we can understand our past by gazing in surprise at the futures we once held dear’. Expo ‘70 reminds us of what was to feel optimistic and excited for the future, the promise of technology and the capacity of human beings to respond to it in hope rather than fear. As Osaka prepares to host another Expo in 2025 with the theme Designing Future Society for Our Lives, this hope is as essential as ever.

By Rebecca Morrill and Guy Tindale, August 2020

Essay by Rebecca Morrill + Guy Tindale

Various images are © creative commons license

Related

Imaginary Sonic Visions by Bill Fontana is a sonic response to Enrique Sobejano and Fuensanta Nieto’s unrealised design for NCCA Moscow: New National Center for Contemporary Arts in Moscow – Competition Finalist.

IMAGINARY SONIC VISIONS

Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos

w/ Bill Fontana

Hannah Peel created her track by following the flow of Lily Jencks’ drawing. (The Horizon: your steps are a metronome. 30 minutes, 23 July 2020.)

THE HORIZON: YOUR STEPS ARE A METRONOME.

30 MINUTES, 23 JULY 2020.

LILY JENCKS w/ HANNAH PEEL

Yuri Suzuki re-imagines Richard Roger’s Zip-Up House as a musical instrument created via acoustic simulation of the space.

ZIP-UP HOUSE

Richard Rogers

w/ Yuri Suzuki

Meditations on “Theatrum Mundi”, is a sonic response in 12 movements by Yuval Avital to Daniel Libeskind’s “Theatrum Mundi”, 1983, a series of 12 abstract works (paper, collage and paint on board) that give visual form to a premonition of the future as a city besieged by an unknown infection. The composition interprets the visual artworks as ‘mandalas’ and their titles as poetic vectors.

THEATRUM MUNDI

DANIEL LIBESKIND

w/ YUVAL AVITAL

Akrafokonmu/Soul washer's badge was written, performed and produced by Chisara Agor in response to Elsie Owusu's A Gallery for Returning Treasures.

A GALLERY FOR RETURNING TREASURES

ELSIE OWUSU

w/ CHISARA AGOR

Essay

Back to the Future: Revisiting the World Expo

by Rebecca Morrill + Guy Tindale

PiM.studio Architects, A music hall in the Alps, Valsolda, Italy, 2019 – competition

ARCHITECTURE MEETING NATURE MEETING SOUND

PiM.studio

w/ mcconville

Essay

Sound In Time and Step with Architectural Space

by Clare Farrow

Loraine James presents a visionary sci-fi dreamscape for Ab Roger’s cocoon-like structures.

LIVING WITH BUILDINGS

AB ROGERS

w/ LORAINE JAMES